Walking the talk: Indonesia tries low-carbon rice — and the results are already visible

On a sunny day in Boyolali, terraced fields stretch across the landscape as farmers, officials, researchers, and rice traders move through them reflecting together on how knowledge has shaped new production norms, including stopping flooding of paddies every day.

It is, on paper, a modest change. But for Indonesia — one of the world’s largest rice producers, and a country balancing the tensions of climate change, water stress, and pressing livelihood issues to tackle — it is part of a much larger shift. Low-carbon rice is no longer a blueprint discussed in meeting rooms. It is being grown, milled and—quietly—eaten.

This month, 10 representatives from across the rice value chain travelled through Central Java to see what that shift looks like up close. Their visit marks a milestone in the Low Carbon Rice Project (LCRP), launched in 2022, funded by the European Union and led by the mission-driven Preferred by Nature. The project’s premise is deceptively simple: if farmers, mills and local governments can align around better practices, Indonesia could cut emissions, restore soil health and build a rice sector resilient to the pressures bearing down on it. Most compelling is that this premise is not unique to Indonesia—it offers a model that can be applied across rice-producing countries worldwide.

‘We used to irrigate every day. Now we plan.’

In Tanjungsari Village, where green paddies stretch to the foothills, the changes are tangible. Here, RICEsilience supports demonstration plots managed by 25 lead farmers per site, each applying SRP principles with the help of agricultural extension officers and Rikolto staff.

“We reduced fertiliser use by 50%,” says Mrs Jujuk, one of the farmers leading the programme. “Before, we irrigated daily. Now we follow the crop cycle and irrigate only when needed.”

The shift follows the introduction of Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD) — a water-saving method proven to cut methane emissions while maintaining yields. Combined with more precise fertiliser use, it represents a small revolution in practice.

Village Head Supriyanto says the social glue matters as much as technique:

“Farmers in the SRP programme are active — they share lessons, progress, challenges. Our role is to enable and accompany.”

For Ratih Rahmawati, Co-Program Manager of RICEsilience at Rikolto, this collaboration is the backbone of progress.

“Low-carbon rice depends on close cooperation between farmers, field officers, cooperatives and local governments,” she says. “That’s how we build a sustainable system.”

Inside the mill: Where diesel engines fall silent

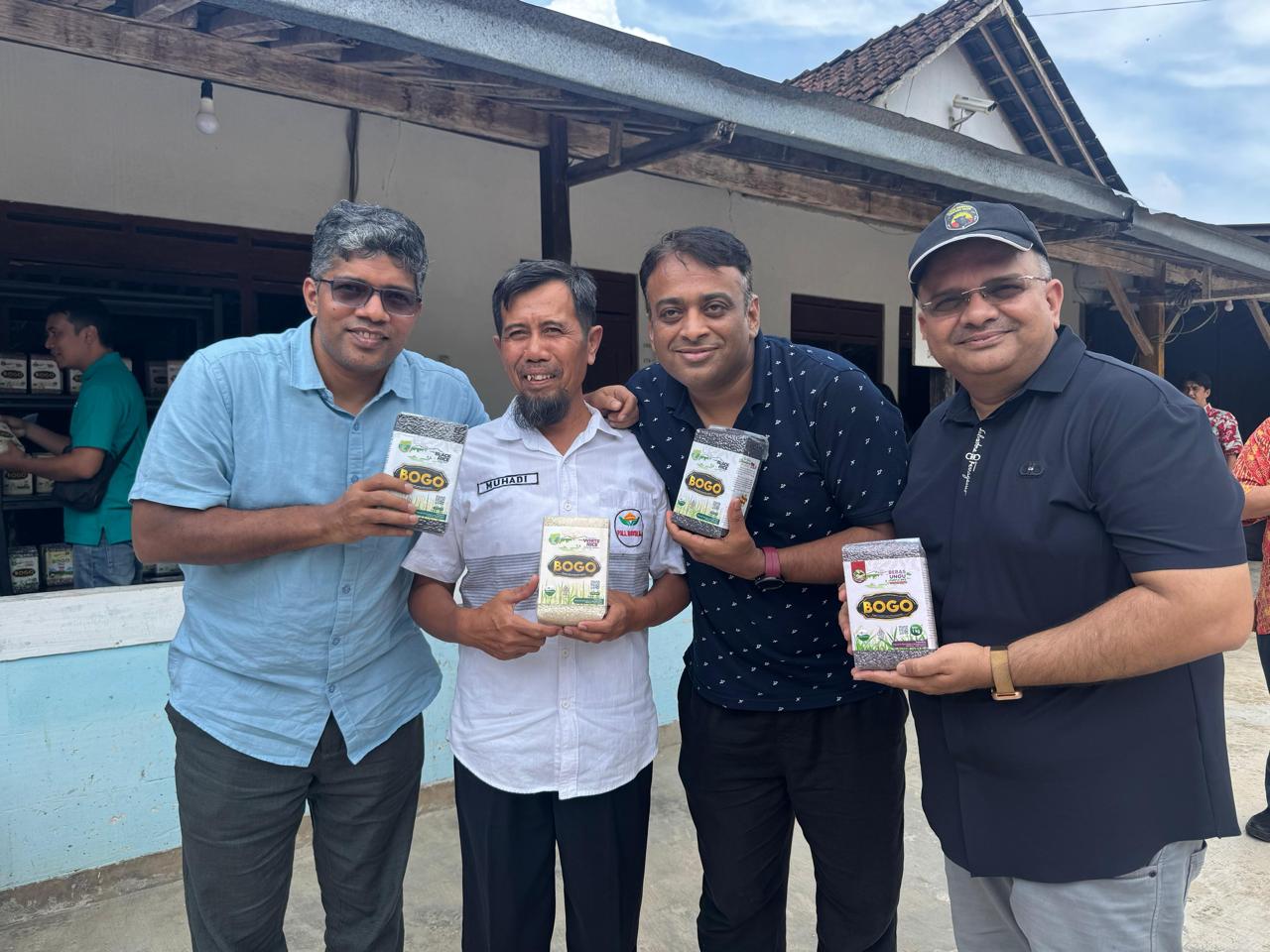

A short drive away, the group stops at Bogo Foods, a mill producing organic red, black, brown and white rice — about 16 tonnes a month.

Its owner, Muhadi, shows visitors the electric machinery that replaced his old diesel set-up. The upgrade, supported through LCRP, is part of a broader shift: organic certification, transparent sourcing from 90 farmers, and plans for full product traceability through QR codes on packaging.

“Being part of global initiatives exposes us to feedback from outside Indonesia,” says Muhadi. “It forces us to innovate.”

Local officials are enthusiastic. Bambang Jiyanto from the Boyolali Food Security Agency, accompanied by senior extension officials Gunawan and Arifah, praised the mill’s transformation.

“This is the kind of ‘natural’ production we want to see more of,” they said in a joint statement.

Observers from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) were equally impressed.

“There is a clear vision driving this transition,” noted Dr Prakashan Chellattan, IRRI’s Senior Agricultural Economist.

From field to plate: Low-carbon rice hits the menu

Perhaps the strongest sign of momentum lies beyond fields and mills. Low-carbon rice from LCRP-supported mills is already being served in Central Java.

At Boemisoera, a restaurant in Semarang, customers eat dishes made exclusively with Bogo Foods rice.

“Offering low-carbon rice is part of the story,” says operations manager Vivi Susanto. “Consumers want to contribute to positive change — we give them a way to do it.”

During a roundtable discussion that followed the field visit, stakeholders from IRRI, the Kerala Climate Resilient Agriculture Project, the World Bank, local NGOs and farmer facilitators agreed: demand is emerging, but scaling it requires coordinated support from government and markets.

“Indonesia shows a strong, forward-looking vision,” emphasises Aadarsh Mohandas, Preferred by Nature’s Global Commodity Lead for Rice.

Policy momentum begins to stir

Beyond farms and restaurants, the project has nudged policy forward. LCRP has submitted six policy drafts across East and Central Java, and in 2023 Indonesia established a National Working Group for the Sustainable Rice Platform. It brings together stakeholders from across the value chain — farmers to millers, scientists to government — to push for long-term reform.

For a sector where policy, science and farming often operate in separate silos, this coordination is rare.

A four-year attempt to reinvent Indonesia’s rice system

The Low Carbon Rice Project (LCRP) set out to tackle these challenges across five regencies in East and Central Java. Its approach blends the technical with the political: farm-level training, energy transitions for mills, and a vision to gather public and private stakeholders into the same room.

Four years in, the numbers are striking.

- 2,600 farmers are now linked to 13 mills through structured production partnerships.

- 68 small mills have swapped diesel engines for electric power — cutting operational costs by up to 40% and emissions by around 15%.

- Draft policy recommendations have been delivered to five district governments, pushing for regulations that reward sustainable practices.

The project is run by a coalition: Preferred by Nature; PERPADI, the rice millers’ association; and KRKP, an organisation advocating for food sovereignty. Running alongside it is RICEsilience, funded by CISU and implemented by Preferred by Nature, Rikolto and KRKP. RICEsilience works with the same farmers, but through the lens of the Sustainable Rice Platform (SRP) Standard — the closest thing the rice sector has to a global sustainability benchmark.

Together, the two initiatives are stitching something unusual into Indonesia’s rice economy: an end-to-end chain that is lower-carbon, traceable and demonstrably better for both producers and soils.