A British forester in Panama: Timothy Synnott on what FSC must do next

At the FSC General Assembly in Panama City, founding Executive Director Timothy Synnott reflects on three decades of certification, governance, and the need for FSC to stay focused on its core mission - and to remember the value of saying “no.”

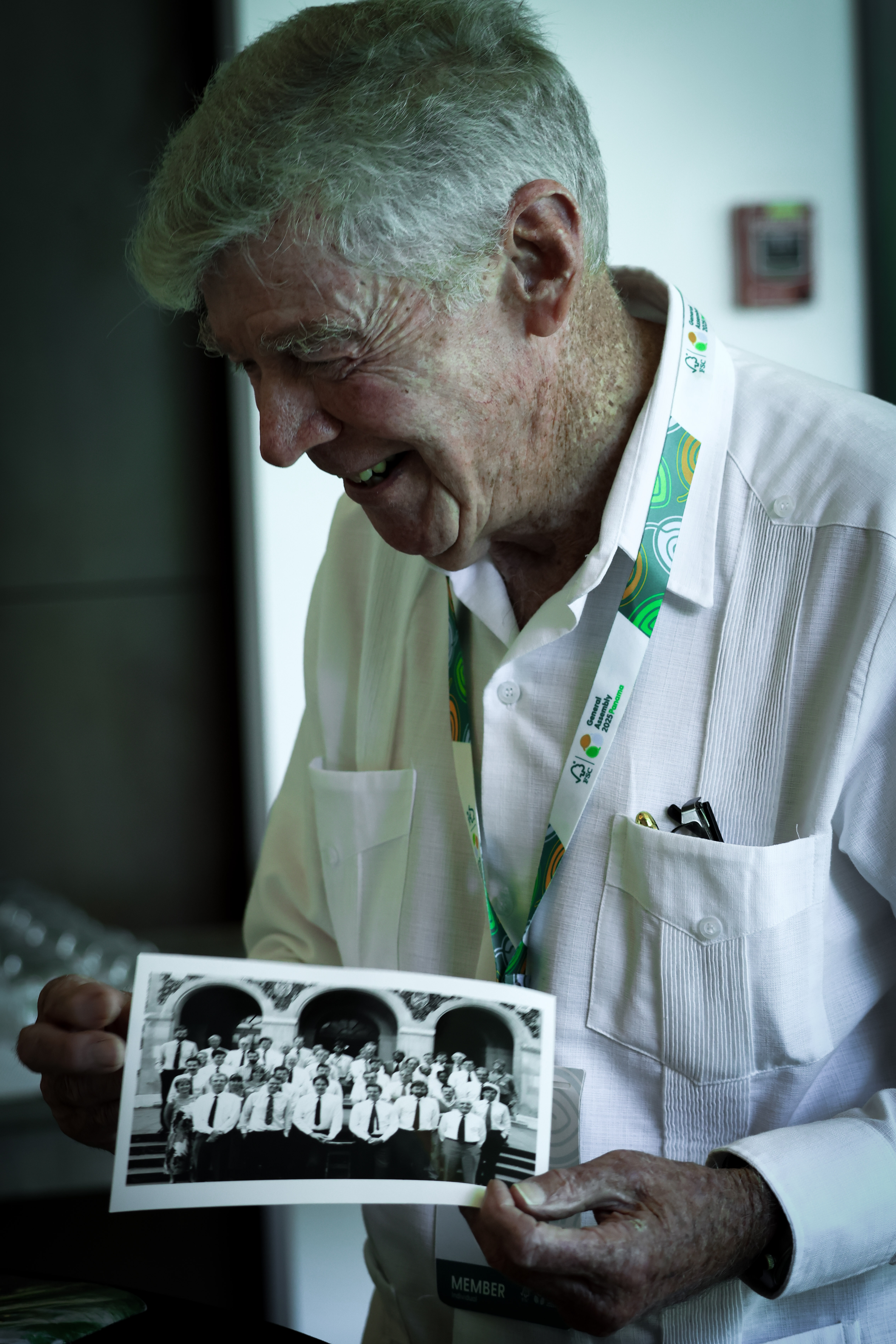

In the humid shade outside the conference centre, Timothy Synnott looks entirely at ease. His lively eyes, dry humour and clipped English phrasing make him stand out among the hundreds of delegates gathered for the Forest Stewardship Council’s General Assembly. It’s been more than thirty years since he helped launch the organisation, yet his engagement with its fortunes has barely dimmed.

“I’ve lived most of my life in the tropics,” he says matter-of-factly. “Uganda for eight years, and the last thirty-five in Mexico. So this heat doesn’t bother me.”

Timothy Synnott speaks with the vitality and vigour of someone much younger, frequently drawing on anecdotes from a long life of travelling.

From Somerset to the tropics

“I was born in Somerset during the war,” he says. “My father was in the Navy and wanted us well out of the way. I grew up in the countryside, and I always knew I wanted to work outdoors. I could never be a farmer, but I thought I could be a forester.”

After studying forestry at Oxford, he left for Uganda. “I worked there as a district forest officer - tropical forests, plantations, savannas, extension work. It was a broad education,” he recalls. “Later, I stayed on to do a doctorate at Makerere University. Idi Amin was the chancellor then, so technically my PhD was awarded by Idi Amin. Nobody dared question its credibility.”

Founding years of FSC

Synnott traces his involvement in FSC back to a London meeting hosted by the British retailer B&Q.

“They were the first large company visibly concerned about where their timber came from. They asked me to look into their suppliers—furniture makers, kitchen manufacturers, in Europe, China, and elsewhere. Some were fine; others raised questions. It showed that you could not manage risk without a consistent, credible system. Not slogans, not promises - a system.”

When FSC was founded, Synnott was drawn into its formative discussions. “By the time of the founding assembly, I was already involved with many of the people behind it. I had worked with governments, NGOs, companies, and understood the different positions. So when they started looking for an executive director, I said I was interested. It felt like the natural next step.”

“All these new ideas are good — restoration, carbon credits, ecosystem services - but if they distract from FSC’s core, they become a problem.”

Timothy Synnott

First Executive Director of FSC (1994–2001)

“Once you lose trust”

More than thirty years later, Synnott views FSC with both familiarity and concern. The chain-of-custody system is under serious pressure: “In the early years, the system could include an element of trust. The auditor would visit regularly, get to know the operation, and that continuity gave a degree of confidence. But FSC now manages a very long global supply chain, with many links.”

He continues, “That makes this whole concept of auditing much more complicated, and therefore the auditing has to be made much more reliable, and that's a slow process. So that's where the trouble is now. If you lose people's trust, it takes years to build it back.”

Synnott is also clear that FSC cannot afford to dismiss outside critique. “Perhaps it's not just bad press. Maybe there's a reason that the criticism is coming. I expect that in some of these organisations, they've done their homework. If those criticisms are not addressed seriously and transparently, it damages confidence in the system. And that’s bad for FSC, bad for its partners, and bad for the credibility of certification as a whole.”

Governance and the right to say no

Synnott believes that FSC’s democratic structure remains both its strength and its vulnerability. “It’s a democratic organisation, and that has been very valuable. But there’s a perception that member decisions are binding in a legal sense. They’re not. The Director General and the board must retain the right to say no - or to say not yet, or not on this scale.”

He pauses before adding, “There has to be a way to decline or postpone without it being seen as resistance. Otherwise, you end up with too many initiatives, and no prioritisation. Saying no, when necessary, is part of good governance.”

He has long argued that the board needs more professional support. “We don’t need a corporate-style board, but we do need people with experience of directing large organisations. They could be brought in as advisors - before, during, or after board meetings - to say, ‘Good idea, but think about cost, timing, and risk.’ That wouldn’t be expensive, and it would strengthen decision-making considerably.”

The risk of losing focus

For Synnott, one of FSC’s main challenges is maintaining focus. “There’s a sense now that FSC is spending too much effort strengthening FSC itself rather than focusing on its core task - promoting responsible forest management through certification” he says. “We see proposals for carbon credits, restoration, ecosystem services. All important topics, yes, but if they distract from FSC’s primary function, they become a problem.”

“FSC already has a large income from its core business - its certification and the use of its logo,” he continues. “That should be enough to deal with its central challenges. The risk comes when the organisation expands into every good idea that appears. Each new topic adds cost and complexity. Expansion should follow a clear strategy, not public enthusiasm.”

NGOs, influence, and accountability

Synnott also reflects on how the wider landscape of environmental advocacy has changed. “Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth no longer play the confrontational role they once did. Many national NGOs rely on government or business funding, so their independence is limited. They do good work, but they can’t criticize their funders.”

He smiles faintly. “Someone mentioned influencers as the new watchdogs. I find that idea strange. For me, that was a surprise, but maybe they are part of the answer. Some influencers, not the ones talking about fashion or makeup, but those talking about sustainability and consumption, reach audiences that NGOs no longer do. If they can demand accountability, that could have a powerful impact.”

A measured optimism

Despite his critique, Synnott remains optimistic and is highly impressed by the staff members he has now met. “They're new people. They're younger. There are more women, rather than elderly men. My first experience has been that they are very vigorous.”

He sums up his perspective succinctly: “FSC was set up to promote good forest management through certification. If it keeps that focus and makes sure the system is credible from end to end, the logo will continue to mean what people believe it means. That’s what matters.”

About Timothy Synnott

Timothy Synnott served as the first Executive Director of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) from 1994 to 2001. A British forester educated at Oxford, he has worked across Africa, Asia, and Latin America for six decades.

Now based in northern Mexico, he continues to advise on sustainable forestry and certification systems.

Last call to save the FSC?

For three decades, the Forest Stewardship Council has led the charge in responsible forest management, becoming the most successful certification system to date. But as FSC prepares for its 10th General Assembly, it faces pivotal challenges. Issues of integrity, traceability and trust threaten its survival. In this series leading up to the GA, we turn to key figures who have influenced — and will be shaping — FSC’s journey and ask: How can we secure its future?

Join Preferred by Nature at the FSC General Assembly 2025.